Conflict, controversy and censorship in the arts

From ‘immoral’ imagery to conflicts over identity, the nature of controversy in the arts has changed.

From online safety to two-tier justice and de facto laws on blasphemy, trends that we debated at Living Freedom summer school a few weeks ago have since been in the headlines and throw up significant challenges to those keen to defend freedom.

No less important are developments in the world of culture. The summer school took place against a backdrop of demands that anti-Israel rappers Kneecap should be banned from playing Glastonbury. This week, as noted by Living Freedom speaker Rob Lyons, we have seen Jewish acts banished from Edinburgh festival. As discussed on the Arts First podcast, this is part of a growing trend for artists to experience antisemitism through cancellation. In the recently published Afraid to Speak Freely, campaigners Freedom in the Arts exposed the growing climate of fear, censorship, and ideological conformity in the arts.

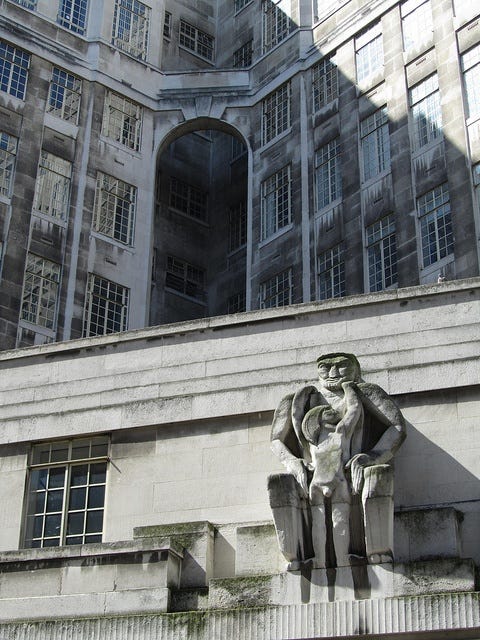

Our summer school took place in a venue whose rich history includes its own artistic controversy that generated demands for censorship. 55 Broadway, the iconic Art Deco building at St James’s Park is currently awaiting redevelopment by Blue Orchid Hospitality. But almost a century ago, controversy was inflamed by the commission of two public sculptures, Day and Night, by Jacob Epstein (1880-1959), which challenged the then accepted boundaries of public art.

Today, intolerance and accompanying demands for censorship often revolve around issues of identity. But as the writer and curator Ella Nixon explained at Living Freedom, a century ago it was questions of morality and accompanying issues of aesthetic taste that so exercised opponents of these sculptures.

Today in the first of a series based on discussions at the summer school, we feature an adapted version of Ella’s talk. And we highly recommend you visit and subscribe to Ella’s Substack.

Alastair Donald, convenor, Living Freedom

Scandalous public sculpture in interwar London

Ella Nixon

Look up from the pavements of London and quite often your eyes will catch a work of art, hidden in public sight.

Nestled behind Green Park and rising atop the entranceway to St James’s Park tube station, the iconic Art Deco 55 Broadway building is no exception in this regard. Both its architecture and sculptural flourishes are paeans of modernist design. The building itself was constructed between 1927 and 1929 as the headquarters for Underground Electric Railways Company of London (now the London Underground). Architect Charles Holden (1875-1960) commissioned artists — including Henry Moore and Eric Gill — to produce eight sculptures that would sit at a high level to reference the ancient Greek Tower of the Winds in Athens. However, public attention focused on the work of Jacob Epstein (1880-1959), who had been commissioned to produce two additional sculptures to occupy a lower flank of the building. Day (1929) depicts a sinister patriarch surrounding a naked young boy, whilst Night (1929) portrays a dying son laid across a woman’s lap. The former of these two sculptures inflamed public controversy.

Why does contemporary art provoke controversy?

Contemporary implies the present, and the term ‘art’ implies value. Thus, contemporary art is a declaration about current standards of worth. Retrospective vision makes it much easier to identify which artworks pushed boundaries and became genre defining. Until then, disputes over what constitutes ‘art’ and ‘not art’ bubble under the feet of working artists.

Epstein was no stranger to controversy. Born in the US in 1880, he spent time in Paris before moving to London in 1907, where he settled and spent most of his life. In conventional histories of British art, his name is held in esteem similar to that of Henry Moore (1898-1986) and Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975), two other prominent British sculptors. His renown is largely associated with the financial success eminent from his over one-hundred cast bronze busts, which populate public galleries across the country: for example, Esther (1930), on display at the nearby Tate Britain. Busts provided security, whilst his more avant-garde ideas were tested in carved public sculptures.

Day and Night (1929) were unveiled in 1929 to an audience that found the sculptures so shocking that a campaign ensued to have them removed. To modern eyes, why might this be the case?

Most glaring when looking at Day is the flagrant exposure of male genitalia. Nudity in art has always invited censorious eyes. Think to classical sculptures of men and women, whose pudenda are oftentimes concealed by delicately placed carved leaves. Not long before the Broadway House commission, Epstein had already sparked controversy in 1907 for creating 18 nude sculptures for what was the British Medical Association Building (BMA) on the Strand (now Zimbabwe House). Commissioned to pay homage to the great men of medicine, Epstein instead installed large naked figures in a public space. The South London Press reported on 26 June 1908:

Father Vaughan, referring to the figures on the front of the British Medical Association's offices in the Strand, said he was sorry to say there were those who advocated the erection of certain statuary which would desecrate public buildings in the highways.

They were all entitled to hold their own opinions about the nude in art, but let them keep the nude in its proper place, where it would not appeal to the more vicious in human nature.

Let them keep such statuary in their art galleries and museums, or where people had to go out of their way to find it.

Like the BMA commissions, the public display of nudity represented on 55 Broadway invited criticism. However, Day hit another nerve altogether due to accusations of paedophilic imagery, in that a naked boy stands at the lap of an adult figure.

Indictments of immorality quickly followed its unveiling. A contemporary commentator, the classical archaeologist Percy Gardner, felt that the sculptures lacked ‘morality’. Some senior London Underground staff even resigned in protest. These reactions can be interpreted in light of the social role attributed to public sculpture. For Charles Jagger (1885-1934) — another recipient of public commissions across London, including the Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner (1921) —sculpture had a definite social role in that it portrayed ‘the peoples, customs and great achievements of its time’. In this context, what message did Day convey?

It’s clear that some members of the public found the sculpture an insult. Many criticisms concerned the length of the boy’s genitalia, leading Epstein to shorten the penis by an inch. By most accounts, this slight adjustment calmed the public furore. Specifics aside, for Epstein the depiction of nudity was a means to reach a universal truth. Primitive figures represented mankind in noble and heroic form. Study in Paris in the 1900s had sparked his appreciation of Indian and West African art traditions – penned ‘primitive’ and seen in the work of Picasso. His move to London in 1907 saw him develop an active interest in the antiquities at the British Museum, especially the African, Greek and Ancient Egyptian galleries.

Epstein found beauty in so-called primitive sculpture, whilst some critics expressed outrage at their perceived ugliness. For such critics, these issues spanned wider than purely aesthetic taste and formal qualities. The hegemony of Greco-Roman tradition — a line that had descended over centuries from the Italian Renaissance, including its ideal standards of proportion and beauty — had been directly attacked and corroded by his non-European influences, in what constituted an insult to Western culture. On display in a public place, the sculptures thereby raise questions about the political repercussions of artistic taste.

Conflictual opinions over the sculptures represent different stakeholders, each with set ideas about which artistic standards to aspire towards. These debates continue into the present day, and can be seen played out in discussions pertaining to architecture and the programming and acquisition strategies of public galleries. Endorsed by state funds, key stakeholders ultimately elevate some artistic standards over others, and thereby feed notions of value to the envisaged public.

One prominent example of how these processes play out at the governmental level was the appointment and subsequent sacking of the philosopher Roger Scruton (1944-2020) as the chairman of the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission in the UK (2019-2020). His conservative writings provide insight into how so-called ‘ugly’ public art might be judged as immoral. Scruton believed that modern architecture – its architectural ornaments and sculptural flourishes – expresses the modern city’s godlessness. Aside from the so-called ‘immoral’ imagery, Scruton believed in Western or classical models of beauty. Thus, a major responsibility is attributed to public sculpture: moral civic life and public life go hand-in-hand to imbue harmony into its subjects.

Defendants would explain Day in the context of Epstein’s wider oeuvre. Namely, a pursuit towards universal truth via the themes and subjects of nudity, maternity/paternity, primitivism and allegory. Thus, these primitive influences frame nudity as a natural element, rather than a political ugliness. Is censorship and vehement criticism the price that one has to pay for veering away from traditional European iconography? Alternatively, perhaps Epstein was another white man profiteering from the ‘Otherness’ of so-called ‘primitive’ societies.

After all, Night and Day have clear non-Western elements in their design. Simple in form, the square-shouldered and flattened adult figures of both sculptures recall and liberally fuse elements from ancient Assyria, Polynesia and Egypt. One contemporary protest was by the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, who argued that the ‘mock simplicity’ of the work was a ‘fad’ of fashion and not in-keeping with ‘the natural beauty of England’. Petrie's words echoed the racist and nationalist attacks Epstein – as a Jewish American émigré – received in his career, which penned his work as alien to Britain and un-English.

Nevertheless, to Western eyes, this depiction – a longing look of the child and exposed genitalia – certainly continues to shock. Epstein was considered ‘avant-garde’ at the time for his pioneering primitivist language. Famously, avant-garde artists were the ones pushing the conventions – the artists excluded from the official Salon in Paris, the economically hopeless Romantics strewn from accepted society – but Epstein was different. Avant-garde yet institutionalised, many of his works feature across the city, on both the street and behind gallery doors. Perhaps this combination of shocking imagery and its institutionalisation were limits pushed too far.

Wherever you stand on the debate, it is astonishing to reflect that most people now wander past the sculpture, blatantly unaware of its controversy. Contemporary art quickly becomes old news, and the shock of the new erodes much quicker than the Portland stone with which it is carved.

Ella Nixon is an art historian, curator and writer. She has written for various publications including the Critic, the ArtReview and The European Conservative.